Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Reflexions from a late September English lesson

Haven’t I ever before heard about Mr David Attenbourough, in the last seven days the scientist-journalist has appeared in my daily conversations in several occasions. It makes me wonder. Is it just casualty or is it something else?

Let me explain in more detail about my encounters with the scientist. It was first during my Wednesday English lesson, while working on an article in the Evening Standard. Pete Clark, one of the newspaper columnists, reported on the death of Australian naturalist Steve Irwin and compared his style to the more ‘traditional’ approach in Attenbourough’s documentaries. I had never heard before about Mr Attenbourough so I didn’t understand the comparison until Margaret, my tutor, explained.

Hadn’t paid special attention to the name, I remembered though when it was mentioned again as part of a Sunday evening pub conversation with my friend Marc. Clearly Irwin’s death has provoked widespread debate, not only because of his popularity but also because his unfortunate accident with a stingray that was captured on film as part of a new series. And due to this current awarness I came across Mr Attenbourough for the second time. Marc started the conversation as ‘have you heard about…?’ (Irwin’s news). And then, as he had also read the Evening Standard article he also referred to Attenbourough. My first reaction when the name came up was, yep!, now I know this person. So I was confident with it – even felt well-informed about giving a sensible opinion. Not to mention how proud I was about the usefulness of my English lessons.

Not having heard enough, my relationship with this now familiar BBC scientist has continued. The third time I was looking at some data on levels of trust across Europe. I nearly screamed in front of my computer when I saw that the most trusted person in the UK, according to a Reader’s Digest survey is, guess whom, yes, in actual fact it is…Mr Attenbourough! Unbelievable. I’ve been in this country for four years now, and it’s not I watch lots of television but I know who Paxman is, or Jonathan Ross. But never saw any of Attenbourough’s programmes and he seems to be even more a celebrity than Kate Moss.

Why? I repeat to myself thinking it is absolutely urgent that I manage to watch one of these out of this world documentaries. It has even become personal. Is somebody telling me that life is miserable without Attenbourough’s being part of it?

After a couple of weeks, I’m trying to look at this story from another perspective. Trying to rationalise. It seems clear that the media agenda determines to a high extent our conversations and interests. So, hadn’t Steve Irwin not died, would I ever have heard about Attenbourough? Probably yes, yet in another context. Which makes me wonder even more because it means that my opinion about this person now has been formed as a comparison to another and not by his own achievements. In spite of this, what really makes me feel a bit annoyed, and definitely very repressed, is how randomly we get to know about things. In a world of liberties, we like to think we are always in control. Yet our choices appear to come up in rather unexpected ways.

Let me explain in more detail about my encounters with the scientist. It was first during my Wednesday English lesson, while working on an article in the Evening Standard. Pete Clark, one of the newspaper columnists, reported on the death of Australian naturalist Steve Irwin and compared his style to the more ‘traditional’ approach in Attenbourough’s documentaries. I had never heard before about Mr Attenbourough so I didn’t understand the comparison until Margaret, my tutor, explained.

Hadn’t paid special attention to the name, I remembered though when it was mentioned again as part of a Sunday evening pub conversation with my friend Marc. Clearly Irwin’s death has provoked widespread debate, not only because of his popularity but also because his unfortunate accident with a stingray that was captured on film as part of a new series. And due to this current awarness I came across Mr Attenbourough for the second time. Marc started the conversation as ‘have you heard about…?’ (Irwin’s news). And then, as he had also read the Evening Standard article he also referred to Attenbourough. My first reaction when the name came up was, yep!, now I know this person. So I was confident with it – even felt well-informed about giving a sensible opinion. Not to mention how proud I was about the usefulness of my English lessons.

Not having heard enough, my relationship with this now familiar BBC scientist has continued. The third time I was looking at some data on levels of trust across Europe. I nearly screamed in front of my computer when I saw that the most trusted person in the UK, according to a Reader’s Digest survey is, guess whom, yes, in actual fact it is…Mr Attenbourough! Unbelievable. I’ve been in this country for four years now, and it’s not I watch lots of television but I know who Paxman is, or Jonathan Ross. But never saw any of Attenbourough’s programmes and he seems to be even more a celebrity than Kate Moss.

Why? I repeat to myself thinking it is absolutely urgent that I manage to watch one of these out of this world documentaries. It has even become personal. Is somebody telling me that life is miserable without Attenbourough’s being part of it?

After a couple of weeks, I’m trying to look at this story from another perspective. Trying to rationalise. It seems clear that the media agenda determines to a high extent our conversations and interests. So, hadn’t Steve Irwin not died, would I ever have heard about Attenbourough? Probably yes, yet in another context. Which makes me wonder even more because it means that my opinion about this person now has been formed as a comparison to another and not by his own achievements. In spite of this, what really makes me feel a bit annoyed, and definitely very repressed, is how randomly we get to know about things. In a world of liberties, we like to think we are always in control. Yet our choices appear to come up in rather unexpected ways.

Monday, September 25, 2006

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

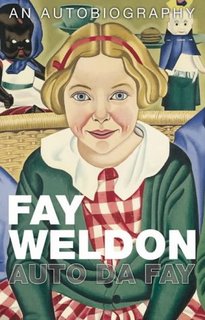

Feminism, Women and Happiness ( from the Observer)

Fay Weldon gives short shrift to the views for which feminists have fought so bitterly over the years. In her latest book, she not only warns high-flying women that they should expect to end up single, she also suggests that sexual pleasure may be incompatible with high-powered careers and that women should simply accept they are less capable of being happy than men.

Fay Weldon gives short shrift to the views for which feminists have fought so bitterly over the years. In her latest book, she not only warns high-flying women that they should expect to end up single, she also suggests that sexual pleasure may be incompatible with high-powered careers and that women should simply accept they are less capable of being happy than men.'If you are happy and generous-minded, you will fake it and then leap out of bed and pour him champagne, telling him, "You are so clever" or however you express enthusiasm,' she says. 'Faking is kind to male partners ... Otherwise they too may become anxious and so less able to perform. Do yourself and him a favour, sister: fake it.'

According to Weldon, sensible members of the sisterhood should, therefore, follow the example so graphically set by the actor Meg Ryan in the 1989 movie When Harry Met Sally, and fake orgasms whenever necessary.

'If you are happy and generous-minded, you will fake it and then leap out of bed and pour him champagne, telling him, "You are so clever" or however you express enthusiasm,' she says. 'Faking is kind to male partners ... Otherwise they too may become anxious and so less able to perform. Do yourself and him a favour, sister: fake it.'

In fact, Weldon's views are surprisingly similar to those of Michael Noer, the news editor of Forbes.com, who caused his own furore last week by advising male readers to steer clear of ambitious women or face a lifetime of misery and discord. 'Marry pretty women or ugly ones, short ones or tall ones, blondes or brunettes, just, whatever you do, don't marry a woman with a career,' he wrote in an article that sparked outrage on both sides of the Atlantic.

Weldon, however, goes even further that Noer. She does not restrict herself to comments on how women should conduct their sex and careers. Instead, her book covers eating, social life, the family and shopping. The latter receives high praise: 'The urge to acquire is in your genes,' she writes. 'Don't beat yourself up about it. Just remember, 12 pairs of shoes is fine but 24 pairs is pushing it.' Overall, very few things make women happy - and even fewer of them, suggests Weldon, are matters of substance. 'Ask a woman what makes her happy and she comes up with a list: sex, food, friends, family, shopping, chocolate. "Love" tends not to get a look-in. "Being in love" sometimes makes an appearance. "Men" seem to surface as a source of aggravation,' she writes.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)